If the IRS rejected your Offer in Compromise (OIC), you’re not alone—the IRS rejects a large portion of OIC applications. In fact, out of 30,163 OIC proposals in FY 2023, the IRS accepted only 12,711, representing approximately 42% of the proposals. This means the majority of offers are not approved on the first try. A rejection can feel discouraging, but it’s not the end of the road. You have several options available under federal IRS procedures to resolve your tax debt, whether you’re an individual taxpayer or a business owner. This article will guide you through understanding why your offer was rejected and outline the steps to take next—from filing an appeal (Form 13711) to submitting a new offer or exploring alternative IRS relief programs.

Why Was Your Offer in Compromise Denied?

Before you take action, confirm that your OIC was rejected and not simply returned by the IRS. There’s a significant difference:

- Returned Offer: A return means the IRS sent your OIC application back without thoroughly reviewing it, often due to a procedural or eligibility issue. For example, the IRS will return an offer if you fail to include the $205 application fee (and don’t qualify for a fee waiver) or if you’re missing required forms. They may also return it if you have recently submitted a similar offer that was rejected or if you aren’t in compliance with current tax filing and payment requirements. Returned offers cannot be appealed; you must address the issues (e.g., include missing information or wait if you submitted too soon) and then resubmit a new OIC application.

- Rejected Offer: A rejection means the IRS has evaluated your offer (determined you’re eligible and processed your application) but has decided that your offer amount istoo low. In a rejection letter, the IRS typically explains that it believes you can afford to pay more than what you offered based on your financial information. Common reasons for rejection include the IRS determining that your reasonable collection potential (RCP)—the amount they believe they can collect from your assets and future income—is higher than your offer, or they think you could fully pay the debt through installments instead. Essentially, the IRS concluded that accepting your offer “as is” isn’t in the government’s best interest.

If your offer is officially rejected, the IRS will notify you by mail, and you’ll receive an OIC rejection letter. That letter should state the reason(s) for rejection and include financial detail tables (Income/Expense and Asset/Equity Tables) showing how the IRS calculated your ability to pay. Review these enclosures carefully. Identify which items the IRS disagreed with. For example, perhaps they valued your house or business higher than you did or disallowed some of your expenses. This will help you decide your next steps.

Both individual taxpayers and business owners can have OICs rejected for similar reasons. The process in the future will also be identical for personal and business tax debts. Still, it involves different financial forms: individuals submit financial information on Form 433-A (OIC), while businesses use Form 433-B (OIC). Suppose you’re a business owner whose company’s OIC was denied. In that case, you’ll want to review the business asset valuations and income calculations the IRS made (e.g., accounts receivable, equipment equity, etc.), just as an individual would review their assets and income. In either case, you have rights and options available to you after a rejection.

Your Rights After an OIC Rejection (Appeal Process)

Don’t panic: An OIC rejection is not final if you take timely action. The law (IRC § 7122) grants you the right to appeal an IRS rejection of an Offer in Compromise. In other words, you can request that the IRS’s Independent Office of Appeals review the decision. This appeal is an administrative review within the IRS, separate from the division that issued the rejection, and it can result in the offer being accepted or modified or the rejection being upheld.

Appeal Deadline: You have 30 days from the date on the rejection letter to submit an appeal request. Act quickly, as missing the 30-day window will result in a final rejection, and you will lose the right to appeal. The IRS rejection letter will typically include instructions for where to send your appeal request.

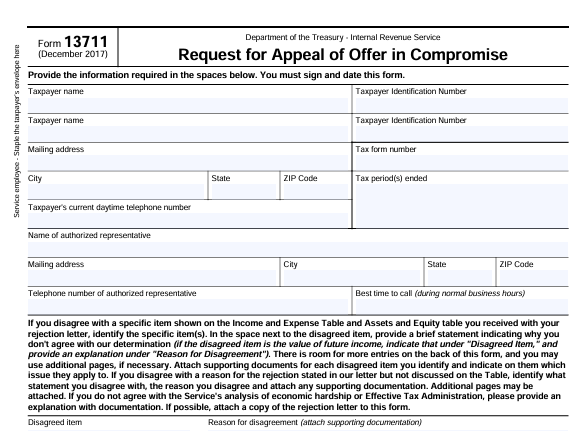

How to File an Appeal: To initiate an appeal, you can file Form 13711, Request for Appeal of Offer in Compromise, with the IRS. Form 13711 is a one-page form where you’ll fill in your identifying information and list the specific items you disagree with from the IRS’s analysis. On the form, for each “Disagreed item” (for example, the value of your home or the amount of disposable income calculated), you provide your “Reason for disagreement” and can attach supporting documentation. Essentially, you’re building a case as to why the IRS’s decision was wrong or should be reconsidered:

- If the IRS overstated your ability to pay, provide evidence to support your claim. For instance, perhaps they thought you have $20,000 in equity for a vehicle, but you owe most of that on an auto loan—you could provide loan statements to show that the actual net equity is much lower. Or perhaps they categorized some expenses as unnecessary; you could show that those costs are necessary and reasonable. Address each point of disagreement with relevant supporting facts, such as bank statements, appraisals, and pay stubs.

- If you believe the IRS didn’t consider exceptional circumstances (such as severe hardship), explain that. The IRS can accept an offer based on Effective Tax Administration (ETA) or public policy/equity reasons in rare cases. For example, if requiring full payment would cause exceptional hardship even though you technically could pay. If you argued for a hardship exception and were rejected, reiterate your circumstances in the appeal with any new evidence.

You can also appeal by writing a formal letter instead of using Form 13711. The letter should contain the same information: your details, a copy of the rejection letter, the tax periods involved, an explicit statement that you are appealing the Offer in Compromise rejection, and a detailed explanation of why you disagree with the decision. Be sure to sign under “penalties of perjury” that your statements are true and accurate. Whether you use Form 13711 or a letter, include a copy of the rejection letter and any enclosures, and send your appeal to the address indicated (usually the IRS office that issued the rejection).

Timeline Tip: As long as you mail your appeal by certified mail within 30 days of the date on the rejection letter, the IRS should consider it timely. During the appeals process, IRS collection actions remain suspended, just as they were while your Offer-in-Compromise (OIC) was under initial consideration. This means that the IRS generally won’t levy your assets or attempt to collect the tax while your appeal is pending. They may, however, file a notice of federal tax lien to secure their interest if one isn’t already in place.

What Happens in Appeals: After you submit the appeal, your case will be assigned to an Appeals Officer who was not involved in the original rejection. This person will review your arguments and any new information you provide. They may reach out to you (or your representative) for discussion or to ask for additional documentation. You’ll get the chance for an independent review of your offer. If the Appeals Officer agrees that the original decision overlooked something or was too harsh, they can accept your offer or propose a revised acceptable offer amount. If Appeals ultimately sustains the rejection, they will send you a notice to that effect, at which point the OIC process is indeed closed (at least for that specific offer).

Note for Business Taxpayers: If the offer was for a business (e.g., corporate tax debt or payroll taxes), the appeals process is essentially the same. You would use Form 13711 and provide supporting financials for the business. Be sure to include an updated Form 433-B (OIC) and any relevant business financial statements if there have been changes, just as individuals should update their Form 433-A (OIC) for appeals. The Appeals Office will consider the business’s ability to pay in the same manner.

Why Appeal? In most cases, it’s wise to appeal an OIC rejection rather than accept defeat. You’ve already invested time in the OIC. An appeal gives you another chance without having to start over from scratch. There is no additional IRS fee to appeal (you have already paid the OIC application fee), and you may succeed in obtaining a better outcome or at least gain insight into what the IRS would accept.

Tips for a Successful OIC Appeal

- Ensure your appeal is postmarked within 30 days of receiving the rejection letter. Late appeals are usually dismissed.

- Be specific in your disagreements: Point out exactly where you believe the IRS’s calculation is incorrect. For example, “The IRS counted $15,000 in my savings, but $12,000 of that is from a nontaxable VA disability benefit that shouldn’t be included in the collection potential – see the attached benefit letter.” The more precise and factual, the better.

- Include supporting documents: Don’t rely on assertions. If you claim your house is worth less than the IRS estimated value, include a professional appraisal or comparable sales. If you need a higher allowable expense for medical costs, include receipts or doctor’s statements. Your goal is to provide Appeals with new evidence or context that the original examiner may not have had.

- Consider professional help: If the stakes are high, you may want to consult a tax professional, such as an Enrolled Agent, CPA, or tax attorney, who is experienced in OIC appeals. They can draft a persuasive protest and ensure you don’t miss any opportunities to strengthen your case. An experienced representative will be familiar with IRS guidelines and know how to negotiate with Appeals. Sometimes, a tax professional can identify grounds for acceptance that you might overlook.

- Stay compliant during the process: Continue to file any required tax returns and pay current taxes on time while your appeal is pending. Compliance is crucial; the IRS won’t settle if you’re falling behind on new obligations.

An appeal is your opportunity to correct mistakes or present new information. However, if, after reviewing your case, you conclude that the IRS was correct (for example, maybe they can collect more than you thought), then appealing to argue without new evidence may not be fruitful. In that scenario, you can consider the other options discussed below instead of a formal appeal.

Submitting a New Offer in Compromise (Reapply or Second Offer)

If appealing the rejection isn’t viable or unsuccessful, the next option is to submit a new OIC application. There is no strict waiting period to reapply after an OIC rejection. If your financial situation changes significantly, you can submit a new OIC. However, you should not simply resend the same offer again without any changes. The IRS may view a repeat offer with no new information as frivolous. If you submit essentially the same offer again, the IRS can reject it immediately. Additionally, one of the reasons the IRS returns offers without review is if “you recently submitted a similar offer that was rejected”, meaning they expect something to be different before considering a new offer.

When to consider a new OIC: Reapplying is worthwhile, particularly if your financial circumstances have improved from an OIC perspective. For example, since your last offer was rejected, perhaps:

- You lost income or had a reduction in wages.

- You incurred higher necessary expenses (e.g., new medical bills, increased living costs, etc.).

- Your assets have decreased in value, or you have sold an asset and used the proceeds, resulting in less equity available.

- Some of your tax liabilities are nearing expiration (the 10-year collection statute is running), which can reduce the practical future income component the IRS calculates.

Significant changes like these can lower your reasonable collection potential, meaning an offer that was too low before might now be acceptable. If such changes exist, document them and consider submitting a new offer based on your new financial reality.

Improving your offer: Even if your financial situation hasn’t changed significantly, you may choose to offer more money in a new Offer in Compromise (OIC) to meet the IRS halfway. The IRS rejection letter or appeal might indicate an amount they’d accept (sometimes, examiners or appeals officers will tell you, for example, “We recommend acceptance if you offer $X more”). At a minimum, the financial analysis tables included with the rejection provide a clue. If the IRS determined that your net realizable equity plus future income equals, say, $30,000, and you only offered $10,000, you now know why they said no. In a new offer, you could increase the amount closer to $30,000 if you have a way to fund it.

- Example: Suppose your initial offer of $5,000 was rejected because the IRS calculated your reasonable collection potential to be $15,000. If your circumstances haven’t changed, an offer near $15,000 (or at least something substantially higher than $5k) would likely be needed for consideration. Alternatively, if you have now lost your job and your only income is unemployment, your RCP might have dropped, and a lower offer could be justified, but you’d need to demonstrate that change with new financials.

Process for a new OIC: Reapplying means starting a fresh application: you’ll submit a new Form 656 (Offer in Compromise), new collection information statements (Form 433-A(OIC) for individuals and/or 433-B(OIC) for businesses), plus the application fee and initial payment again. Keep in mind:

- You must remain current on all filings and payments, including all required tax returns. If you have ongoing tax obligations, such as quarterly estimates or payroll deposits, these must also be paid on time. Any lapse in compliance can immediately derail a new OIC.

- When the IRS reviews a second offer, they will notice what’s different. Provide a cover letter or explanation that highlights any new facts (e.g., “Since my last offer, my income has decreased by 30%, as shown in the attached pay stubs,” or “I am offering an increased amount, using funds I’ve borrowed from family, to reach an acceptable offer”).

- Be prepared to wait several months for processing again. The timeline for a new OIC could be similar to the first, often lasting 6 to 9 months or more. If your new offer is very clearly improved (either by circumstance or amount), it stands a better chance.

- Note that the statutory appeal right (IRC § 7122(e)) applies to each distinct offer. If your second offer is essentially unchanged and is immediately rejected as frivolous, you wouldn’t be entitled to an appeal on that because it was never considered. So make the new submission count.

Do not repeatedly submit offers as a stalling tactic. Due to past abuse of the OIC program, the IRS and Congress have implemented measures to discourage frivolous or repetitive offers. As mentioned, a knowingly false or substantially similar offer can trigger a $5,000 penalty under IRC § 6702 for a “specified frivolous submission.” Only submit a new OIC if you have a genuine basis for a different outcome.

When not to reapply: If your financial situation is more substantial now than it was before (e.g., you’ve secured a higher-paying job or acquired assets), reapplying will likely result in an even higher calculated ability to pay, making an OIC even less likely. In such cases, or if you cannot increase your offer to the level required by the IRS, it may be time to consider alternative resolution strategies outside of an OIC. The following section outlines other IRS debt relief options.

Alternative IRS Debt Relief Options (After OIC Rejection)

A rejected offer in compromise doesn’t mean you have to resign yourself to the IRS immediately, collecting the full debt in one swoop. The IRS has other programs and collection alternatives that can help manage or reduce your tax burden. Here are the main options to consider:

Installment Agreement (Payment Plan)

An Installment Agreement is a plan to pay your tax debt in monthly installments over time. If you cannot pay in full now but can afford monthly payments, an installment agreement is often the next best option after an Offer in Compromise (OIC). The IRS offers various installment plan options:

- Guaranteed Installment Agreement: If you owe $10,000 or less, the IRS is required by law to approve a payment plan, provided you can pay the full amount within three years.

- Streamlined Installment Agreement: For individuals who owe up to $50,000, the IRS can approve a simplified plan, which requires no detailed financial disclosure, with a payment term of up to 72 months (approximately 6 years). Businesses with smaller liabilities may also qualify for streamlined terms on specific amounts.

- Non-Streamlined Installment Agreement: If you owe more than $50,000 or require a payment plan longer than the streamlined term, you can still request one, but you’ll likely need to provide financial information (Form 433-F or 433-B, etc.) and negotiate the terms.

- Partial Payment Installment Agreement (PPIA): This is a special type of installment plan where you pay less than the full amount of the tax debt before the collection period expires. Essentially, the IRS agrees to accept smaller monthly payments that won’t fully pay off the debt by the end of the 10-year statute of limitations, and any remaining balance at that expiration is forgiven. A PPIA requires demonstrating you can’t afford to pay the entire balance, even over time. The IRS will review your finances periodically (usually every two years) and could increase payments if your situation improves. A PPIA is somewhat like a longer-term, pay-as-you-can approach; interest and penalties still accrue, but it provides relief by not forcing an unaffordable amount and ultimately forgiving the remaining debt if time runs out.

To set up an installment agreement, you typically submit Form 9465, Installment Agreement Request, or apply online for certain balances. If your debt exceeds $50,000 or you require a PPIA, you’ll also submit financial statements for IRS review. Keep in mind that interest and penalties continue accruing on any unpaid balance until it’s fully paid, so the longer the plan, the more you ultimately pay. Still, an installment plan can prevent enforced collection (like levies) as long as you make the payments, and it provides a structured way to chip away at the debt.

Note: If your OIC was rejected, entering an installment agreement does not prevent you from trying an OIC again in the future. Some taxpayers opt for a payment plan for a while, and if their situation later worsens or a substantial portion of the 10 years has passed, they may reapply for an Offer in Compromise (OIC). Please ensure compliance with filings and payments during the installment plan.

Currently Not Collectible (CNC) Status

If you are genuinely unable to pay anything—even minimal installment payments—you might qualify for Currently Not Collectible (CNC) status. CNC is not a forgiveness of the debt but rather a temporary hold on IRS collection. The IRS will mark your account as “not collectible” if forcing payment would create an economic hardship, meaning you have no disposable income after meeting necessary living expenses. All collection activity stops while you’re in CNC: no levies, no payment demands (aside from reminder notices), and any active wage garnishments should be released. The IRS could still file a lien.

To obtain CNC status, you’ll need to submit financial information (typically Form 433-F or 433-A, accompanied by supporting documentation) to demonstrate that your income is only sufficient to cover basic living expenses and that you have no significant assets to liquidate. For a business, CNC status can be approved if the company is unable to pay (although for an operating business, CNC is less common unless the business is closing or generating only enough to cover its expenses). The IRS will review the financials, and if they agree, they’ll designate the account CNC.

Important considerations with CNC:

- Annual Review: The IRS may periodically review your ability to pay, typically on an annual or biennial basis. If your income increases or your expenses go down, they can remove the CNC status and resume collection.

- Statute of Limitations Continues: While in CNC, the 10-year collection clock continues to run. If you stay in CNC until the statute expires, the debt could ultimately be written off. However, be aware that if you default on compliance (for example, don’t file a future return), the IRS can revoke CNC.

- Interest/Penalties: These continue to accrue during the CNC period. You’re essentially postponing the problem in hopes that it either expires or your situation improves. It’s a valid safety net if you genuinely can’t afford to pay now.

CNC is often a relief for those with hardships—for example, someone with a lot of medical bills or a person who’s unemployed and barely meeting basic needs. Just remember that it’s temporary.

Other Considerations

- Penalty Abatement: Although not a collection alternative per se, you can also explore abating (removing) specific penalties if you had reasonable cause (e.g., a serious illness, a natural disaster) or if you qualify for First-Time Penalty Abatement. Reducing penalties won’t eliminate the tax debt, but it can lower the balance and, therefore, the amount you need to resolve. This can sometimes make an installment plan more affordable.

- Bankruptcy: In extreme cases, certain tax debts can be discharged in bankruptcy if they meet specific criteria, including income taxes that are more than three years old and other specified conditions. Bankruptcy is a last resort option and beyond the scope of this article. However, if your Offer in Compromise (OIC) was rejected and the tax debt qualifies, discussing Chapter 7 or Chapter 13 bankruptcy with a bankruptcy attorney might be worth considering. Keep in mind that not all taxes are dischargeable, and the IRS Offer in Compromise (OIC) and bankruptcy have distinct advantages and disadvantages.

- Offer in Compromise – Doubt as to Liability: If your OIC was rejected because the IRS believes you can pay more, but you believe you don’t owe the full amount, that presents a different issue. A “Doubt as to Liability” OIC (when you dispute the correctness of the tax) may be an avenue if you have evidence that the assessed tax is incorrect. Those are less common, and typically, one would pursue an audit reconsideration or appeal to address liability. However, it’s worth mentioning that OICs can also be used for liability doubts or exceptional circumstances (Effective Tax Administration).

The bottom line is that even after an OIC rejection, you still have options to manage your debt. Compare your options—appeal, try again, or opt for a payment plan or CNC—and choose the option that best fits your situation. The following table provides a side-by-side comparison of these post-rejection strategies:

Comparison of Post-Rejection Options

To help you decide on your next step, here is a comparison of three primary options after an OIC rejection: Appealing the rejection, submitting a new OIC, or pursuing an alternative (such as an installment plan or CNC status). Each has its timeframe, requirements, and considerations:

| Appeal Rejection (to IRS Appeals) | Submit New OIC (reapplication) | Installment Plan or CNC (Alternative Resolution) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| When to Choose | If you believe the IRS made an error in evaluating your offer or you have additional evidence to support a lower offer amount. Must be within 30 days of rejection. | If you missed the appeal deadline or Appeals upheld the rejection, and your financial situation has changed significantly (or you can offer more) to meet IRS requirements. | If you missed the appeal deadline or Appeals upheld the rejection, and your financial situation is the same. |

| Process & Forms | File Form 13711 or an appeal letter explaining why you disagree. Include a copy of the rejection letter, a list of disputed items, reasons, and supporting documents for each. Mailed the rejection letter to the office. Handled by the IRS Appeals; typically resolved within a few months. | Submit a new Form 656 with all attachments (e.g., 433-A(OIC), 433-B(OIC) for businesses, etc.) and a new $205 fee, along with the initial payment. Essentially a fresh OIC application. Must again be verified and processed by IRS Collections. It can take several months to over a year. | Can sometimes be completed without financials online or may need to submit Form 433-F, Form 433-A, or Form 433-B. |

| Pros | Allows independent review.A Settlement Officer may overturn or modify the rejection. There is no new application fee. Keeps collection on hold during the appeal. | Fresh opportunity. You can adjust the offer amount or wait for more favorable circumstances (e.g., a lower income). If the situation improves (from your perspective), a new offer might succeed where the old one failed. | Avoids collection action by the IRS, like levies or wage garnishments. |

| Cons | Time-sensitive. Action must be taken within 30 days. Outcome not guaranteed – Appeals may agree with the rejection, which can be time-consuming. Meanwhile, interest on your tax debt accrues during the process. | Repetitive and costly: Requires paying the fee (unless low-income) and possibly a higher initial payment again—resulting in another long wait with no guarantee of acceptance. | Does not permanently resolve the issue, unless it’s an agreed where the debt is repaid in full. |

| Effect on Future OIC | An appeal, if successful, results in your offer being accepted – so no future OIC is needed on that debt. The appeals process itself has no negative impact on submitting offers later. | A second OIC is treated like a new case. Multiple failed OIC attempts can make the IRS less sympathetic unless circumstances genuinely change. | If you go on a long-term installment, you can still apply for an OIC later, but you’d typically pause or terminate the installment to do so. Being in a CNC or installment plan indicates that you’re attempting to resolve the debt, which is a positive step. However, any new OIC would need to account for any payments made. There is no direct limit on subsequent OIC attempts; however, OIC will consider that you have managed to pay (or have improved your financial situation) when calculating any offer. |

As the table shows, an appeal is a great first choice if you qualify, as it doesn’t cost more and could potentially overturn the decision. A new OIC is suitable if you can significantly improve the offer or if a new development makes a better case. Other resolutions, such as installment plans or CNC, provide a safety net if an OIC doesn’t work—they don’t reduce the debt, but they can prevent IRS enforcement and offer manageable terms.

Examples: Moving Forward After a Rejected OIC

Sometimes, it’s helpful to see how others have navigated this situation. Here are a couple of realistic scenarios (names changed) illustrating different paths after an OIC rejection:

Example 1 – Appeal Leads to Acceptance: John, an individual taxpayer, owed about $500,000 to the IRS. He offered $5,000 in an OIC, citing that he had very little in assets and was financially tight. The IRS rejected his offer primarily because they believed John had approximately $20,000 in equity in his home (they had a valuation higher than John’s) and that his monthly income, minus expenses, would allow for more payments over time. John was discouraged but filed an appeal within the 30-day window. In his appeal, he included a fresh appraisal of his home showing that due to market changes and the mortgage balance, the equity was only around $5,000 (not $20,000). He also provided documentation that some of his expenses, which the IRS categorized as excessive, were necessary, including a high medical cost for a condition, supported by doctors’ statements. During the Appeals conference, the Appeals Officer agreed that the original offer didn’t account for these factors. John decided to modify his offer to $8,000, taking into account a minor error on his part regarding a savings account. The IRS Appeals accepted the $8,000 offer—a win for John, who ultimately settled his $500,000 debt for $8,000. This outcome was the direct result of appealing and providing better evidence; had he not appealed, he would have faced the entire $500k bill or been stuck in an extended payment plan.

Example 2 – New Offer After Changed Circumstances: Maria owned a small landscaping business and incurred a $30,000 payroll tax debt during a challenging year. She submitted an OIC on behalf of her business to settle the debt for $10,000. The IRS rejected the offer, noting that the business still owned equipment and trucks with equity and that Maria’s finances, as the business owner, indicated an ability to pay more over time. Maria did not appeal because, frankly, the IRS was correct – at the time, the business had some valuable assets. Instead, she entered into a monthly installment agreement of $500 to avoid collection action. Unfortunately, a year later, the business suffered a significant loss of a contract, and Maria had to sell some equipment to cover expenses. At this point, the business’s ability to pay $500 per month dropped sharply. Maria contacted a tax professional, who advised her to submit a new OIC. Now, her offer showed that the business assets had been liquidated (and the proceeds used to pay suppliers and part of the tax, thereby reducing the balance) and that the business’s future earnings prospects were significantly lower. She offered $5,000, which was basically what could be scraped together from the remaining assets. Because her situation had dramatically worsened, the new offer was accepted (after several months of review). In this case, Maria’s first offer was rejected, and an appeal wasn’t pursued, but by waiting until circumstances deteriorated and then reapplying, she achieved a compromise. If the business had improved instead, her strategy might have been to stick with the installment plan or consider CNC if it were to fold; however, she adjusted based on her changed financial situation.

These examples highlight two important lessons: 1) An initial rejection isn’t the final word – appeals can succeed if you address the IRS’s concerns. 2) Timing and circumstances matter – an offer that fails one year might be accepted the next if your financial picture changes (for better or worse).

FAQ: Common Questions After an OIC Rejection

Don’t Go It Alone

Facing a rejected Offer in Compromise can be stressful, but remember that you still have options and rights. Whether you choose to appeal, adjust, reapply, or opt for a payment plan or temporary hardship status, the key is to take prompt, informed action. The IRS collection process will continue, so it’s essential to stay one step ahead by securing your next resolution strategy.

Don’t be discouraged by a setback. Many taxpayers ultimately settle or resolve their tax debts after initial rejections by staying persistent and using the available tools. By understanding the reasons for refusal and following the guidance outlined above, you can make the best of the situation and move toward relief from your tax burden.

Consider getting professional tax help to guide you. As we’ve emphasized, navigating appeals or new OICs and deciding between options like installment agreements or CNC status can be complex. A seasoned tax professional can analyze your financials and the IRS’s stance, help you prepare a compelling appeal or offer, and negotiate with the IRS on your behalf. They can also ensure that you remain in compliance with all IRS rules throughout the process, which is critical to any resolution. Tax professionals are familiar with IRS procedures and can often spot solutions that you might miss.

If your OIC was rejected, don’t give up. To get help, consider setting up a consultation with a tax pro to get some professional guidance on your situation. A little bit of insight and support can help you get closer to your tax resolution goals. Set up a free consultation with Paladini Law now by calling us at 201-381-4472 or scheduling online.